I hesitated calling this post ‘the everyday sublime’. The sublime I want to recommend doesn’t occur every day in the same way. On the contrary, it is an event interrupting daily repetition. It pulls new values into the everyday.

Nonetheless, this sublime is everyday in the sense of within our daily experiences. That shouldn’t mean ordinary. I rejected ‘the ordinary sublime’ as a possible title, along with ‘the common sublime’. Ordinary misses the point that the everyday sublime is a breach, an interruption, where difference enters the ordinary. This breach isn’t spectacular, like a volcanic eruption, yet it has all the hallmarks needed for the sublime: it is an event; it overwhelms us; pulls us in different directions; transforms us; and prompts us into action.

The everyday sublime is extraordinary in the sense of out of the ordinary (their kindness touched me in ways I had not expected) rather than in the looser sense of outstanding (they are extraordinary athletes). The sublime is about a transforming event, not a ranking.

Common is a better term, but it has acquired pejorative connotations – as lowly, encountered too frequently, or overly shared. That’s a shame because one of the most important aspects of the everyday sublime is its connectivity.

The sublime is extraordinary partly because it comes from an overwhelming connection to others (including animals, nature, technologies and objects). It’s the opposite of what some writers might want to indicate when they use ‘common’ as a term of disdain: “If you’ll forgive me, he’s common…” (A Streetcar Named Desire – of course, he’s anything but).

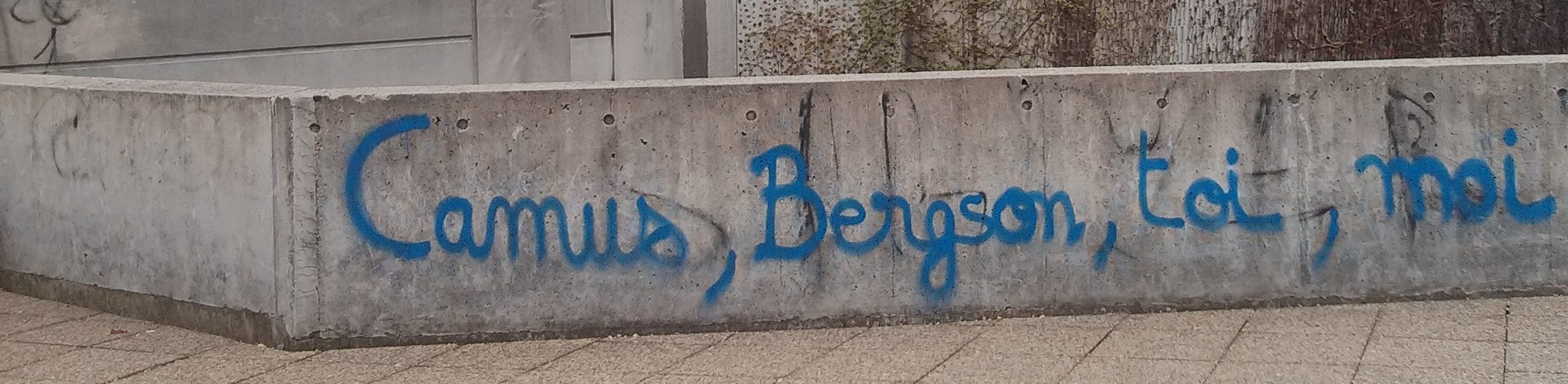

They are wrong to disparage shared experiences and their power to elevate us together. As we’ll see when I turn to two examples from literature, the everyday sublime is an uncommon value we hold in common. This makes it more significant, not less. Instead of indicating a rare attainment we compete for, it introduces values of joint transformation.

When we hear the words ‘extraordinary’, ‘uncommon’ and ‘sublime’ we often think of greatness, grandeur and immensity. These associations lead to a dual mistake. They are wrong about the nature of the sublime and misleading about sublime values, because they confuse the high end of a scale with importance.

The everyday is transformed and intensified by the sublime, bringing novelty into staleness and reinvigorating lives. This does not mean repetition is necessarily dull, but rather than the energy and value of everyday experiences tend to dim with familiarity, until sublime events draw them out again.

Against the supposition of rare and sublime magnificence, we are less likely to encounter something truly sublime in a situation judged and expected to be great. This is because the sublime is made and learned; although its manufactured nature is frequently overlooked in theories of the sublime.

Like other thrilling and exciting experiences, we seek out the sublime, create it once it has been identified, and try to go through it again, to re-create it. ‘Sublime’ is a label for something to be desired and hence looked for and reconstructed – the excitements of cinema or adventure.

If an experience is prepared and sought out in this way, it is harder for it to be sublime. Shock, tension and transformation are conditions for sublimity. When we have some expectation of something, its occurrence is less of a surprise.

When an event is made and hence partly understood, the tension between the resulting emotional reactions and accompanying ideas is framed and therefore less strong. For this reason, planned entertainments on a grand scale – tourism, sport, architecture or spectacle – are always unpromising occasions for the sublime. It is much better for it to strike in the everyday, where it is more likely to truly occur and to make a real difference.

The lofty and the outsize lend themselves to be faked – fabricated – in contrast to the small and fragile. When this happens, they are negative projections, where finitude (limitation in space and time) is confronted by something supposedly outsize and ungraspable – the Kantian idea of sublime excess.

Though there can be sublime experiences in grandeur, they are rare and shouldn’t be taken as the standard for the sublime. On the contrary, greatness is often constructed out of a misleading belittling of the everyday, where finitude supposedly needs to be and is taught to yearn to be saved or transcended through its encounter with a sublime copied from ideas of the divine.

Negativity and its silent but deeply inhibiting effects are the reasons why I have also avoided defining the everyday sublime in opposition to excess. The everyday sublime isn’t not-grandeur, not-greatness, not-immensity. It’s much better than that, because it saves experience from scales ruined by entrenched power structures, where the sublime becomes an instrument of rule through claimed access to the secrets or mystery of the infinite.

Defined positively, the everyday sublime is an event that transforms common experience, when something we encounter everyday, in our usual environments, triggers new and intense feelings, combined with a tension between contradictory and ambiguous desires, all brought together by a series of acts responding to the event.

This sublime – each experience of the sublime and each theory of the sublime – is political. The everyday sublime is a form of resistance. It eludes and offers alternatives to power, when authority works through the devaluing of ordinary lives thanks to ideas and images of greatness, reachable only through the intercession of those holding power and deciding upon values. The power of image-makers and empire builders.

Though it might strike suddenly, this everyday event cannot be instantaneous, since it plays out with the act. It cannot be uncomplicated or unproblematic, since it is determined by opposed tensions. The sublime event must be life-affirming, as it brings greater intensity into life. This should not be confused with pure pleasure or goodness. Intensity is painful and difficult, yet also pleasurable and enticing. Its opposite is boredom and dullness, not pain or evil.

The sublime of the everyday and of resistance is given a literary definition in Pascal Mercier’s Night Train to Lisbon, a book partly dedicated to this ‘noble’ sublime and its power to connect and transform lives:

NOBREZA SILENCIOSA. SILENT NOBILITY. It is a mistake to believe that the crucial moment of a life when its habitual direction changes forever must be loud and shrill dramatics, washed away by fierce internal surges. This is a kitschy fairy tale started by boozing journalists, flash–bulb seeking filmmakers and authors whose minds look like tabloids. In truth, the dramatics of a life-determining experience are often unbelievably soft. It has so little akin to the bang, the flash, or the volcanic eruption that, at the moment it is made, the experience is not even noticed. When it deploys its revolutionary effect and plunges a life into a brand-new light giving it a brand-new melody, and does that silently and in this wonderful silence resides its special nobility.

Pascal Mercier, Night Train to Lisbon, trans. Barbara Harshav, London: Atlantic Books, 2008, p 38

Mercier’s book unfolds around moments of the everyday sublime: an encounter on a bridge, the trembling hands of an ageing prisoner, a book left behind by another reader in a beloved bookshop, a surprise reflection in a shop window. Given by perhaps the central character of the book, the definition of silent nobility is a commentary on its characters and their lives.

Careful to deny greatness and over-dramatisation in the sublime, Mercier replaces them with a discrete and slower force. The almost imperceptible event is sublime though, as shown by the transformation brought about by the event. The intensity of the sublime does not have to be showy (‘kitsch’) but does have the power to revolutionise a life.

The silence of the sublime indicates its place in the everyday. It is hidden within the ordinary and repeated things of a life, but changes them forever by giving them new energy and meaning. Silent nobility is common connection, a commitment between different lives around a shared infusion of value into the everyday and thanks to the everyday.

Mercier’s novel is a tribute to Pessoa. The Book of Disquiet is quoted at the beginning of Night Train to Lisbon. It gives the later book one of its story lines and many of its themes. Both books are written under pseudonyms, but that’s an unimportant detail when compared to their joint pursuit of the everyday sublime. Here is one of Pessoa’s versions of the event:

Today, walking down the Rua Nova de Almada, I happened to gaze at the back of a man walking ahead of me. It was the ordinary back of an ordinary man, a simple sports coat on the shoulders of an incidental pedestrian. He carried an old briefcase under his left arm, and his right hand held the curved handle of a rolled-up umbrella, which he tapped on the ground to the rhythm of his walking…

This man’s back is sleeping. His entire person, walking ahead of me at the very same speed, is sleeping. He walks unconsciously, lives unconsciously. He sleeps, for we all sleep. All life is a slumber. No one knows what he’s doing, no one knows what he wants, no one knows what he knows. We sleep our lives, eternal children of Destiny. That’s why, whenever this sensation rules my thoughts, I feel an enormous tenderness that encompasses the whole of childish humanity, the whole of society, everyone, everything.

Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet, trans. R. Zenith, London: Penguin, 2002, text 70

Philosophers like to think we find common humanity in great experiences and in our ability to survive or dominate them – in wars, floods, earthquakes, through awesome figures and daunting numbers, or in terrifying and impressive technologies. Pessoa shows how it only truly comes with the everyday, in its paradoxical blend of inevitability and uncertainty, of slumber and overwhelming emotions, and in its resistance to what we do to each other when we are fooled by impressive illusions.