Can a closed social system that uses a common language be autopoietic? If words, grammar and meanings evolve outside the boundary of a system, can the system be autonomous when it employs them?

There is a simple preliminary answer to these questions. A closed system can be autonomous and autopoietic when using a common language, if that use doesn’t open it up to external control of its processes of self-creation. This external command does not have to be intentional; merely able to interrupt and alter autopoietic internal communication.

Though the answer is simple, the problem it responds to is not. Autopoiesis of any form is threatened by needs for external energy, materials and environmental interactions. The solution is to try to build defences responding to those threats.

For social systems, the operations of autopoiesis function thanks to externally evolving and controlled media and materials: language and social beings. Means of production, communication and self-defence have exterior sources, thereby introducing vulnerabilities demanding further layers of protection.

Attack and defence, immunity from outside threats and destruction of intruders are signs and ideas that reinforce militaristic images. They encourage warlike themes: embattled reasoning about ends and means; feelings of fear, vengefulness and bloodlust; fetishes of destructive power and protective might; antagonistic relations between different factions; rankings according to friend and foe, hero and traitor, patriot and foreigner, brilliant generals and expendable troops; absolute senses of right and wrong; obsession with sovereignty and subservience.

A semiology of autopoiesis should register and study this terminology and selection of signs based around defensive boundaries. Its critical role is to analyse and respond to the influence and implications of signs. Here, the consequences of definitions and signs include the privileging of insiders against outsiders and ideas of existential peril justifying extreme responses and, as I’ll show, layered systems of internal policing.

Autopoiesis promotes an image of life as a struggle against external otherness and difference, in the name of self-identity, control and autonomy. It thereby risks replicating the paranoia – mistakenly evident and unyielding lines of thought – of fearful resistance against external and internal threats, whether real or dreamed up.

In the following passage, Niklas Luhmann, one of the foremost thinkers of the autopoiesis of social systems, gives his definition of autopoiesis, adding sovereignty to autonomy, a term little used in definitions taken from biology or artificial systems theory:

… everything that is used as a unit by the system is produced as a unit by the system itself. This applies to elements, processes, boundaries, and other structures and, last but not least, to the unity of the system itself. Autopoietic systems, then, are sovereign with respect to the constitution of identities and differences. They, of course, do not create a material world of their own. They presuppose other levels of reality, as for example human life presupposes the small span of temperature in which water is liquid. But whatever they use as identities and differences is of their own making.

Niklas Luhmann (1990) ‘The autopoiesis of social systems’ in Essays on Self-Reference, New York: Columbia University Press, pp 1-21, p 3

Autonomy and sovereignty are close concepts, but the latter adds the idea of power over a political body: the people is sovereign; Scotland is a sovereign nation. As a historical sign, sovereignty cannot be separated from a struggle, whether it is for which body politic is sovereign, like King, aristocracy, bourgeoisie or workers, or for the sovereignty of a nation from oppressors, or for universal political sovereignty, one that does not imply political inequalities, such as discrimination and persecution based on race, class, gender, sexuality, religion or nationhood. Sovereignty is always contested, because it is about the exercise of power and resistance to it.

Very few of these struggles have avoided violence. Where conflicts have involved nation states, or civil conflicts, they have justified the most terrible acts. To draw autopoiesis into social systems as a central organising sign, alongside sovereignty, does not only raise problems of the possibility of autonomy for such systems, it also situates efforts to achieve it within models of defence and immunity, amplified by the often extreme measures and ideologies of fights over sovereignty.

Semiology must be self-critical to avoid one-sided accounts, prejudice, lack of historical awareness and ill-informed or banal suggestions. There are two standout reasons to be careful about judging autopoiesis and its appeal to defence and immunity for autonomy negatively. First, the appeal might be necessary, rather than a faulty choice. Second, resistance to external threats can be a way to allow internal variety and difference to flourish.

Self-defence and immunity could be requirements for life. When introducing the idea to biology and theory more generally, Maturana and Varela defined life as autopoiesis. Without it life ceases and, therefore, processes protecting it are essential. We might be wary of images and signs of conflict. This does not mean they are dispensable. The problem is then not about violence and autopoiesis, but about the need for violence to sustain life.

Even if autonomy requires independence from external control and hence cutting itself off from sources of threatening difference and change, it does not follow that this isolation must be for an unchanging identity and the avoidance of difference. Quite the contrary, it can serve as a platform or safe space for continuous self-reinvention and creation.

The idea of the necessity of internal difference for autopoiesis is central to Luhmann’s social theory. His argument is that social systems are communication networks dependent on information, utterance and understanding: ‘[these] are aspects that for the system cannot exist independently of the system; they are co-created with the process of communication.’ (3)

Information, utterance and understanding function through novelty. They have to combine into a new occurrence, in order to register as significant and shift the system to a further state. This is an event-based account of communication, where events are necessarily different in the ‘production of the next elements in the actual situation, and these have to be different from the previous one to be recognisable as events.’ (10)

In earlier discussions of autopoiesis I have contrasted strict and loose definitions of autopoiesis. Luhmann’s is exceptionally strict, not because he is trying to map it on to social systems but, more importantly, because he is attempting to explain how the autopoiesis of social systems depends on novelty-generating events.

Strict should not be confused with consistent. Strict means with strong and restrictive conditions. Those conditions could be contradictory. Luhmann means them to be so and this contributes to the strictness of his definition by adding a surprising condition. Autopoietic systems manage paradoxes in a very deep way. They must respond to, but also generate paradoxical events. They are both systematic and unpredictable; contained and difference-creating.

Luhmann adds the following terms to the definition of autopoiesis as self-contained unity of self-production: information; utterance; understanding; event; action; decay; arbitrariness; risk; and paradox. This doesn’t mean that they can’t be part of autopoiesis defined more loosely. Cells can be studied as information flows, for instance. It means that they are necessary conditions for social autopoiesis, rather than contingent properties.

Each of the additional terms can be viewed through novelty. Information has to be new to be significant, since repetition of exactly the same piece of information is pointless. You already told me that. An utterance is always new, since it is placed in time at a different instant to those that come before and after it. She said it on Tuesday in the boardroom. Understanding is accretive; it grows through novel acquisitions and reviews. The system understood the raise in temperatures to be a new threat.

There are many definitions of ‘event’ and not all involve novelty. Those that do minimally depend on the same time and space conditions of utterances: an event is new because it takes place at a new time. Luhmann is using a much broader idea of the novelty of event, where there is something qualitatively different in any event and where any event is partly produced by an act. The renegades have created a breach on level 4!

Luhmann defines autopoiesis as interactions within and between two couples: system and environment; event and situation. Environmental and internal differences are events needing to be controlled and situated by autopoietic systems to preserve unity and autonomy. The event of an external breach to the system, communicated through an utterance, must be understood as new information and then reacted to in order to preserve and continue autopoietic processes:

The unity of the autopoietic system is the recursive processing of this difference of continuing or not, which reproduces the difference as a condition of its own continuity.

‘The autopoiesis of social systems’ , p 13

An autopoietic system is constantly reacting to new events. They are not only different as threats, but also induce novel reactions within the system. An event is the occurrence of something different accompanied by the production of a new response, adapting to preserve the autopoietic system – or failing to and ‘not continuing’. This leads to a model based on vigilance to external perils and to internal innovation as responsive self-production.

Vigilance reinforces the militaristic signs autopoiesis is prone to. It also adds imagery of internal threats and counter-measures, found in spying and counter espionage. For Luhmann, an autopoietic system is always monitoring and reacting to its own processes defined in terms of acts.

This event-act-monitoring-act model leads to multiple tiers within the system. It is essential to Luhmann’s definition of autopoiesis because it separates autopoietic systems from those controllable as simply perception-led or reactive. This is a very strict definition of autopoiesis, since it is not necessarily the case that autonomy and self-production rely on acts and communications; they could be automatic and not depend on understanding.

Nonetheless, according to Luhmann, a system event is always an act of selection as communication:

Without a system of three selections – information, utterance, and understanding – there would be no communication but simply perception. By this synthesis, the system is forced into looking into the possibilities of mediating closure and openness.

‘The autopoiesis of social systems’ , pp 12-13

Monitoring, as a constant ‘looking into’ and acting upon acts of selection and communication, divides a system into lower and upper tiers in terms of which actor is monitored. A base level response must be evaluated and responded to at higher levels with the aim of maintaining closure, while also requiring and responding to environmental events. The guard systems have noted a new kind of breach and tried raising the internal shields. Why did they do that? What does it entail for order and autonomy? How to react? This case has introduced a paradox in law. How can it be subsumed into code and precedent?

There is action on all tiers. Lower ones act directly in response to an environmental change. They are most at risk of curtailing autopoiesis due to an outside source. Upper ones evaluate the effects of lower responses, to protect continuing autopoiesis. This does not mean their decisions are immune to error, but rather that breakdown will come from chains of internal acts and counter-acts. Paradox and risk are omnipresent in the system.

In all cases, action is a novel fact with a subject and an outcome; like a new move in one direction rather than another. Luhmann uses the uncertainty of decisions – the way the system doesn’t know beforehand which way a decision will go – to build unpredictability into social systems:

Logically, actions are always unfounded and decisions are decisions exactly because they contain an unavoidable moment of arbitrariness and unpredictability. But this does not lead into lethal consequences. The system learns its own habits of acting and deciding […]

‘The autopoiesis of social systems’ , p 8

This use of learning as self-understanding and control through the evaluation of successful responses is a recurrent feature of autopoiesis. Sometimes it is presented as its great strength. I have discussed the potential flaws and misrepresentations of deep leaning as autopoietic in earlier posts. The significant point for semiology, in the case of autopoietic social systems, is the hierarchy of case and learning in a conflictual situation. Part of the system is judging and either approving or dismissing an act by another lower part of the system under stress from a threat to the system.

I have been using action verbs in describing Luhmann’s theory (judge, approve, learn). It could be objected that Luhmann speaks little about subjects and does not need them as subjects of actions, but his emphasis on decisions as unfounded and unpredictable requires some sort of free subject, where freedom justifies the lack of foundation and where free choice of an option justifies arbitrariness and unpredictability. His autopoietic systems are series of free decisions.

They are also series of decisions about decisions. The manner in which systems learn about themselves and decide on what to do about lower level actions constitutes the many-tiered aspect of social systems. They are defined by peripheries and cores by levels of self-monitoring designed to preserve autopoiesis. This special structure is necessary because the unfounded, arbitrary and unpredictable properties of decision must introduce potentially disruptive differences, triggered either by external or internal prompts.

All of this contributes to making the autopoiesis of social systems a model for crisis management in embattled situations of threat and conflict. This does not only fit images of war, but also of institutional and corporate efforts at survival in menacing environments and amidst internal uncertainty and decay.

In his The Autopoiesis of Architecture: a New framework for Architecture, Patrik Schumacher follows Luhmann’s definition of autopoiesis and adapts it to architecture as discipline, insisting on conflictual situations:

The different function systems confront each other as aspects of each other’s environment, under risky conditions that combine mutual opacity with interdependence. Failure to self-organise effective responses leads to irrelevance and spells extinction.

Patrik Schumacher (2011) The Autopoiesis of Architecture: a New framework for Architecture, Oxford: Wiley. p 191

Like Luhmann’s approach, Schumacher presents architecture as having to be open to a hostile environment where the priority is to preserve the integrity and identity of the discipline strictly on its own terms:

The formula posited is openness through closure. This formula poses the task of continuous adaptation of the system to the relevant changes it distinguishes from its environment. This process of adaptation in turn implies independence/autonomy for the system with respect to the task of organising its response. The impact of the environment does not pervade and directly determine the system.

Patrik Schumacher (2011) The Autopoiesis of Architecture: a New framework for Architecture, Oxford: Wiley. pp 192-3

This leads to an extreme vision of the purity, role and functioning of a discipline and practice, where necessary partners become threats and where different levels of the practice and discipline will be monitoring each other with an eye for treacherous contact or complicity with the outside, leading to this extreme statement on architecture, finance, economics, affordability and society: ‘The theory of architectural autopoiesis insists that financial arguments cannot be integrated into the autopoiesis of architecture.’ (p 225)

On this kind of fortified image of a practice, any part of the discipline seen as betraying the purity of its control over its changing identity will be viewed as putting the whole practice at risk, with all the attendant punishments and measures such a label entails:

Although each individual architect is confronted with little choice over his/her commissions, and his/her concrete tasks are thus set by his/her clients, the avant-garde discourse is autonomous in setting the themes of its defining debates, and in selecting which projects should exemplify the defining tasks, responding to the supposed key societal challenges.

Patrik Schumacher (2011) The Autopoiesis of Architecture: a New framework for Architecture, Oxford: Wiley. p 190

The autopoietic model set out by Luhmann is much more strict even than Maturana and Varela’s. They build interactions between autopoietic systems into their theory, while still keeping the priority of autonomy in those interactions. Luhmann and Schumacher give us a model where ideals of sovereignty and ideological purity, as developed and protected by an avant-garde or higher monitoring tiers, take precedence over collaborations and partnerships, governed by ethics of trust and openness, rather than suspicion and closure.

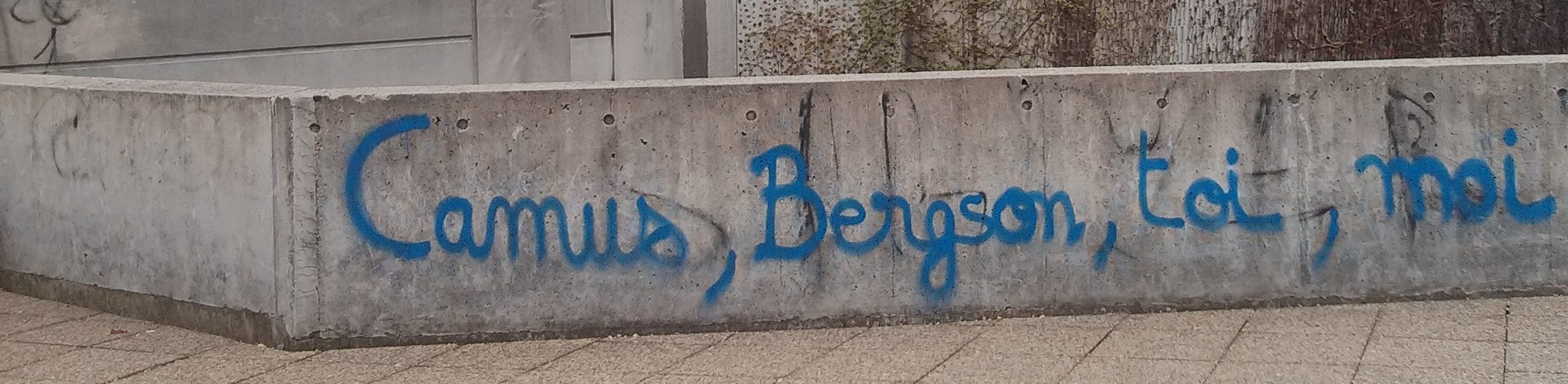

The opposition between openness and militaristic closure explains my choice of the image at the start of this post. It is a plan for Lille citadelle, designed by Vauban in the seventeenth century. Lille is the ‘queen of citadelles’; a major example of the defensive boundaries, layers, bastions, curtains, ramparts and fortified gates devised to protect garrisons. The fort was built to defend Lille, after Louis XIV retook the city from the Spanish.

The citadelle is now a park. It is permeable and open; a place for meeting and passing. It is also a site of remembrance, where 700 trees have been planted to commemorate the political prisoners and resistance fighters of the ‘Loos train‘, the last train to depart for concentration camps in Germany from the Lille area. The majority of prisoners died in terrible conditions, either in transit or in the camps. Many had ended in prison due to denunciations and betrayals from their own side.

France has still not come to terms with the opposition of resistance fighters and collaborators over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, from the Dreyfus Affair to the Algerian War. With the rise of extreme right wing parties like the Rassemblement National, the argument about who really fights for France – and which France – is co-opted by overt and covert aims to exploit racism for political ends, as it was in the second world war, the Algerian war and now in the effort to create fear and hatred between parts of the population to justify a populist politics of harsh repression and fictitious ‘original’ values.

Without the citadelle, Lille might well have been lost again. Without a carefully protected secret network, resistance fighters are vulnerable to treachery and false accusations. The openness of a park might well be a passing moment, dependent on periods of determined defence and protectiveness, where transparency and permeability can be fatal weaknesses.

For a semiology of autopoiesis, the advantages and disadvantages of closure and openness matter because an autopoietic strategy is a choice, not a necessity. The imagery of war, immunity, self-policing, inner monitoring hierarchies and internal purity as control of change should inform any decision about that choice, replacing the existential definition of autopoiesis – be autonomous or die – with a more cautious and time-bound sense of the relative interplay of manifold insides and outsides.

Returning now to language and autopoietic social systems, I emphasised autopoietic when describing conditions of control and immunity, because to use an external language is not necessarily to cause a breach of autopoiesis; for instance, when monitoring the language; taking it as an input or output; or employing it as a support for different and immune autopoietic functions.

This last instance is important, as is the concept of immune for autopoietic systems. Just because it appears that a system is using external signs and forms, does not mean it is using them in ways that make it dependent on external control.

There can be processes ensuring immunity, such as a different use of the same language; or the same use but with barriers to any further external ingress; or the same and different uses, but with constant monitoring and defence mechanisms. For language too, this monitoring depends on a separate tier of processes, splitting the autopoietic process into different levels with different kinds of authority and functions.

An outsider listening to teenagers chatting ironically in the language of their elders might have an impression of understanding, but any ability to intervene effectively will be illusory. A legal system might interact with witnesses in a common language, but the legal debates will depend on a much more specialised and closed discourse. A hacker might gain access to a system but be defeated by virus checkers operating at higher levels of security; easy entry does not guarantee full control.

In a previous post I gave the example of a spy ring for closed social systems. If the ring uses a common language to communicate, it can still be autonomous and its components self-made so long as the language use doesn’t open it up to external interference. This explains why secret codes are pivotal and yet risky.

Once the code is broken or when a spy in possession of the code becomes a double agent, every communication is liable not only to be read externally, but much more importantly produced outside, thereby rendering every message suspect and forcing the spy ring to change. Agent Zig Zag’s False Squid, from the Bletchley Park archives, is a good example of the combination of double-agent, communication of false information and code-breaking:

One of Zigzag’s deceptions, Operation SQUID, aimed to convince the Abwehr that Britain had a new, miracle anti-submarine weapon. The Codebreakers at Bletchley Park helped the Allies track the progress of their deception scheme, keeping an eye out for messages relating to their operations. This series of radio messages were sent by the Abwehr, and relate to Chapman’s Operation SQUID. Intercepted and sent to Bletchley Park, they were decrypted by the section known as Intelligence Services Knox (ISK), specialists in breaking Abwehr Enigma.

https://bletchleypark.org.uk/our-story/agent-zigzags-false-squid/

A deciphered code ends autonomy, yet it also points to the solution to my initial questions. It doesn’t matter whether a spy ring has to use symbols and signs in common circulation, so long as any internal use isn’t breached by an external agent or factor.

A parallel can be drawn between code and agents. It doesn’t matter whether an agent grew up outside the spy ring. It doesn’t even matter whether an agent has a parallel external life. In producing the agent as a spy, fulfilling autonomous functions specific to the espionage social system, the ring can still be autopoietic. The full human existence is irrelevant so long as it does not compromise the secret agent.

It could be argued that spy rings are always broken. The best codes are decrypted. The most surprising figures turn out to have been double agents, even a Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, Director of the Courtauld Institute, MI5 agent and, as it turns out, Russian spy. Anthony Blunt, eminent art historian and establishment figure is a good example of the dangers of dissimulation for spy rings:

The contrast between his pre-war and post-war personas was a consummate performance of the dissimulation techniques and self-control that he perfected in his MI5 days.

Peter Kidson ‘Anthony Frederick Blunt1907–1983’ p 25 https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/documents/1511/02_Blunt_1808.pdf

The techniques required to keep a ring closed and yet effective are the same techniques exploitable to function within a ring as a double-agent, because a spy must be able to operate within wider society secretly: dissimulating the spy within the art historian, but also the communist sympathiser within the spy.

There are two opposed strategies for reacting to the double-edged quality of language, both an opportunity for privacy and for external control. Strict definitions of the autopoiesis of social systems make the wrong choice by defining autopoiesis as necessary and thereby committing to an endless and futile struggle for sovereignty. The right choice is to weigh up relations between preserving some minimal form of internal identity while accepting, celebrating even, its necessary entanglement with what it perceives, at times, to be the outside, but not the enemy.