To be a sense-maker is, in other words, to be actively sensitive to dangerous or beneficial trends in the ongoing coupling with the world. Sense-making thus combines, in nuce and for all forms of life, what for complex minds, like those of animals, can be differentiated into action, perception, and emotion.

Elena Clare Cuffari & Ezequiel Di Paolo & Hanne De Jaegher, ‘From participatory sense-making to language: there and back again’ Phenom Cogn Sci (2015) 14:1089–1125 DOI 10.1007/s11097-014-9404-9, p 1114

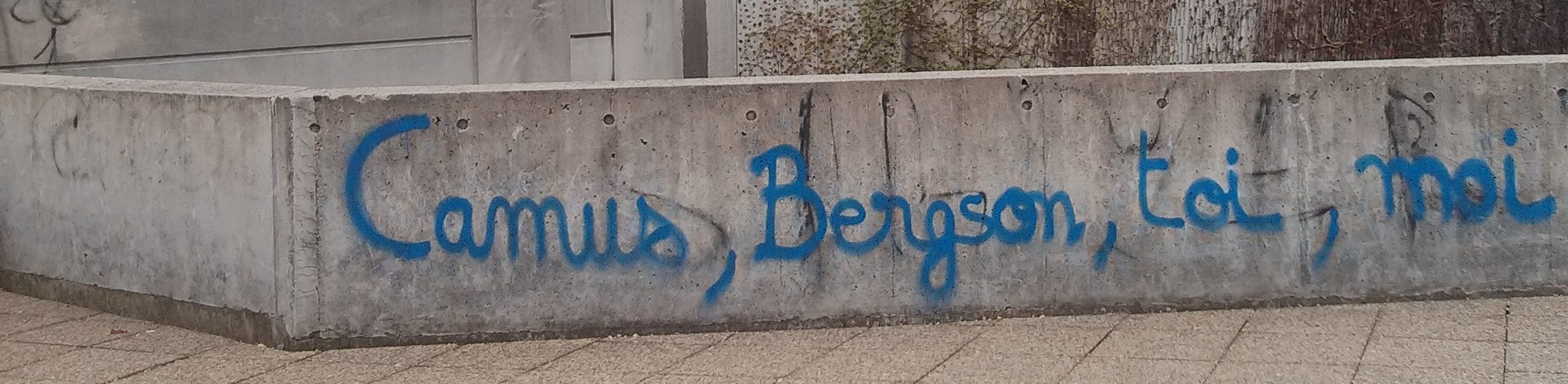

An event has its splendour – it glows – in sense. The event is not what happens (an accident). It is the pure expressed in what happens. This expressed beckons and awaits us.

Gilles Deleuze, Logique du sens, Paris: Minuit 1969, p 175 [my translation, in freestyle]

The two passages above ressemble one another in vocabulary (sense), in context (events or couplings) and, apparently, in their lessons (events happen in ways that can be worthwhile or threatening). They are nonetheless at odds with one another.

The first authors think sense-making is about matching independent internal norms to external encounters as frames for meaningful acts, perceptions and emotions. How should I adapt my personal rules so that I thrive in this encounter?

The second author places sense beyond the reach of meaning, of self-contained individual acts and understanding, and of bodies located in space and time. Sense is all the disembodied woes and splendours that befall us in different and changing configurations in any event (to greet; to betray; to torture; to nurture; to fear; to trust; to destroy; to love…) How should I act to affirm splendour and minimise woe for all and for all time?

The first passage is by theorists of enaction (Elena Clare Cuffari, Ezequiel Di Paolo and Hanne De Jaegher); the second by Gilles Deleuze. Though action is part of both approaches to events and sense-making, there is a fundamental difference. For the former, acts make sense. For the latter, sense makes acts.

When sense is made, the guiding question is about how to act in order to make sense well. When acts are made by sense, the guiding question is about how acts and bodies are made and how to react to the effects of this making.

For the former, the danger is that we might be mistaken about our independent ability to make sense of events. We miss our passivity to the way sense makes us. For the latter, the risk is that sense is too much for us to react to and we fall into despair. Perhaps it is better to assume we can act autonomously, even if this is false?

For enactivists, action is central and fundamental to cognition through the acts of organisms in dynamic interaction with their environments: action in an environment constitutes and is constituted by norm-driven cognition.

For Deleuze, action is peripheral and secondary: action follows from and responds to unconscious prompts that necessarily overwhelm and drive it. Rather than simple action, he calls this counter-actualisation. This is an act countering the many ways events bring woe and splendour into lives as they make them, or actualise into them.

Returning to the apparent closeness of the two passages and positions, enactivists might well claim that they recognise the role of accidental external influences on acts and cognition. Their rules evolve in response to environments. Maybe this is also a form of counter-actualisation. My argument will be that this is not the case. The structure of norms, evolution, environment and action, characteristic of enactivism, denies the prior and overwhelming role of environment in any later act.

I began this discussion with an image. The print is a colonial embellishment depicting its main figures as acting according to their rules for making sense in a novel and challenging encounter: Moctezuma’s gifts and greeting; Cortés’s return of the greeting, but also show of military might and religious right. Yet behind all the overt significations, the meeting was to increase woe for all, in ways that still resound horrifyingly through history and nature. Cortés ended up taking Moctezuma hostage and massacring his people.

There were many uncertain layers of powers, threats and benefits hidden in the encounter: treasures; foodstuffs; disease; political strengths and weaknesses; religious beliefs and force; ways of measuring wealth; slavery; greed and lust; fear and hope; machinery of war; technologies of life such as irrigation and sanitation; pictures of the world; types of government and allegiances; tactics and strategies; different written and spoken languages; geography, fauna, flora and climate; and luck and misfortune are but some of them. Any act resting on norms and meanings will necessarily miss some of them and partly misunderstand all of them in their potential to shape and be shaped by events.

The opposition between the authors is therefore neither in admitting the occurrence of events that wound and challenge us to act, nor in understanding that we attempt to assign meaning to them, nor in that we identify individuals in events. The difference is that Deleuze thinks that these points are insufficient and incomplete. That’s why he defines the event in terms of a pure expressed of neutral infinitives such as ‘to enslave’, in order to preserve the many ways they have and will occur.

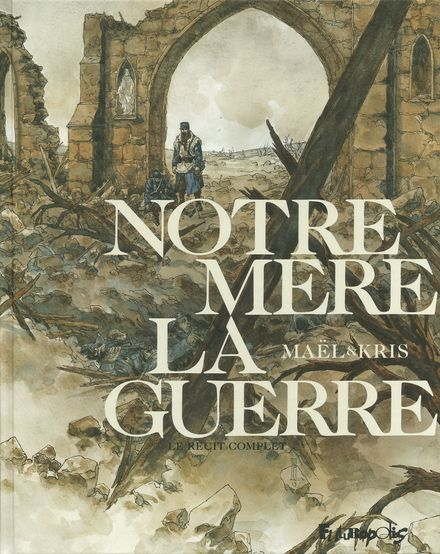

One way of understanding the opposition is through historical wisdom. Is learning from history a steady increase in knowledge and in our capacity to act according to more adequate norms? Or is it a much a more tentative, risky and necessarily inventive counter-actualisation of the potential of events to reoccur, in ways so different that knowledge and norms will be overwhelmed? La der des ders… they said (the war to end all wars, as they called the First World War, to give strength to the troops and to the survivors, but it was to be the mother of all later wars).

Without a sense of the connectedness of all events prior to any subdivision of life, we fail to live up to the events befalling us. Belief in independent individuals, in the sufficiency of meaning for understanding, and in the adequacy of local norms ties us to illusions, unless we abandon the qualifications of autonomy, sufficiency and adequacy.

Events cannot happen to autopoietic individuals, because there are no such self-normed beings. Worse still, if we start with autopoiesis as fact, then we end up with a stunted idea of sense and an inadequate guide for action sensitive to events.

Two critical directions have emerged in my studies of the design, use and application of autopoiesis across many settings. The first has been that the concept is treated very differently in various contexts. Though different thinkers refer to one another and handle autopoiesis as if it has common roots and overlapping meanings, these are in fact inconsistent.

The second critical point is that, for each of these different uses, the concept is internally inconsistent. They impose idiosyncratic and contradictory meanings on the concepts designed to explain autopoiesis. The concept doesn’t have a straightforward definition through other accessible concepts, but rather depends on novel and odd definitions of other concepts. This leads to problematic but often hidden ambiguities, since the unfamiliar word ‘autopoiesis’ is explained through ideas that appear to be more accessible but are in fact used in equally novel and counter-intuitive ways.

For example, the idea of boundary has different meanings in each of the uses of autopoiesis. Its importance and strict application vary. Furthermore, the meaning of boundary ranges from a physical impassible line to a theoretical and ideal limit, yet in all cases these boundaries are crossed, leading to awkwardness about which crossings are permissible and which forbidden. Thus energy is frequently allowed as an innocent passer but commands aren’t. The problem is that energy is a good vehicle for command, through variations in temperature or sustenance, for example.

There’s an interesting by-product to these exercises in solving the inherent contradictions of autopoiesis. Though various approaches lead to different concepts, they can still be related through the methods adopted to resolve common paradoxes. This is why I relate different theories in terms of whether they are strict or loose approaches to the definition of autopoiesis.

The former seek to avoid contradictions by restricting autopoiesis strictly to pure and narrow cases. Ideally and in few cases autopoiesis can operate without contradiction. The latter do so by loosening definitions and increasing their scope. Vague and flexible concepts avoid contradiction and apply to many cases. Both have inherent weaknesses, since strictness tends towards ideal abstraction, where nothing empirical is autopoietic, and looseness tends towards meaningless inclusion, where most things are autopoietic but with very little explanatory advancement and a high risk of confusion.

Were I asked to put the two critical directions in their strongest form, it would be that autopoiesis does not indicate a consistent movement, but rather a loose aggregation of incompatible positions. Individually, these positions are also inconsistent. They impose contradictory and misleading meanings on their core concepts. Autopoiesis defines a school of thought that does not exist as a consistent entity. More seriously, each appeal to the concept imposes unhelpful and distorting sub-concepts. In analysing autopoiesis it is therefore critical to study specific cases rather than any general definition. That’s why each of these posts has focused on particular theorists.

In this post, I will show how these critical directions apply to research on autopoiesis and language, in relation to my opening opposition between different ways of thinking about sense and events. I’ll analyse an article by Cuffari, Di Paolo and De Jaegher where an enactivist variation on autopoiesis takes place through the introduction of a version of dialectics. For enactivism, mind belongs to the life of the body, thus language is explained through the living body, rather than independent and abstract mind. Yet this body is autonomous and has its own norms.

In the application of this dialectical structure by Cuffari et al, the concepts of autonomy and language are reframed according to two models:

The first model is dialectical and conceptual. It details how perpetual negotiations of certain primordial tensions in sociality generate culturally shared horizons of normativity. By this logic, languaging emerges as a special kind of social agency, i.e. a particular solution to a certain progression of conceptual problems pertaining to recurrent tensions between individual and interactive levels of sense-making and between codified/constrained and spontaneous styles of sense-making. The second model is diachronic and developmental. It traces human ontogeny as it unfolds in constant coupling to enlanguaged environments. The logic here is one of individuation out of intersubjectivity via the incorporation of certain sensitivities and powers. This incorporation process yields linguistic bodies—bodies that ‘know how’ to live in language and that reciprocally build and maintain linguistic domains.

Elena Clare Cuffari & Ezequiel Di Paolo & Hanne De Jaegher, ‘From participatory sense-making to language: there and back again’ Phenom Cogn Sci (2015) 14:1089–1125 DOI 10.1007/s11097-014-9404-9, p 1096

The above passage is quite dense and technical. I’ll interpret it and make some critical points. Cuffari et al distinguish two models. They are both dialectical, in the sense of developing through the partial resolution of tensions, but the first depends on the logical analysis of concepts and the latter tracks an actual evolution. From a critical point of view, the distinction of the two models is only relative.

Concepts such as ‘language use’ and ‘action’ aren’t pure and refer to actual cases, though for the authors the actual is given either through highly simplified versions of selected scientific hypotheses or very simple versions of phenomenology.

Simple examples are wonderful pedagogical aids, but they are always deceptive. They should remain illustrations or literary suggestions, open to immediate challenge from almost any reader’s knowledge and experience. They are worthwhile because they connect to life while immediately raising objections and mistrust. A good example is an annoying prompt, rather than a soothing clarification.

The problem with a simple phenomenology is that it lays claim to truth or fact, when it is always a partial extraction from life. The article makes the following claim about smoking: ‘This is why it is so hard to quit smoking. The self-sustaining logic of the habit has been made the body’s own, even if over the long term the habit may paradoxically put the body’s viability at risk.’ (1116)

The flaw here is in the ‘why’. Though habits and their ‘logic’ might be a reasonable initial explanation of the difficulty of giving up smoking, it could only ever be a partial and tendentious approach to addiction, withdrawal symptoms and the effect of endorphins on the brain, let alone the hard vagaries of any life, or the extraordinary philosophical difficulty of defining viability as a universal quality.

If we follow Deleuze’s definition of sense and idea of counter-action, addictions are singular ways in which sense and events determine individuals. There is no general logic to addiction, but rather a communal connection through the way each individual expresses multiple aspects of sense in their own way and through shared actual environments. My body’s way of expressing addiction.

We try to give up smoking in shared worlds and in the grips of connected forces, but each attempt must be singular and not general, because each addiction is singular – hence Deleuze’s insistence on the idea of a life, rather than life in general. I cannot be viable without my singular desires…

There are similar general claims based on reductive phenomenology throughout the enactivist article. The most prominent ones concern learning among young children (mothers gifting toys) and forms of social greetings (involving misunderstanding and the learning through sense making).

I started with a print version of the famed and frequently reimagined encounter between Moctezuma and Cortés, because of this emphasis on gifts and encounters. It seems to me that the aims of enactive autopoiesis lead to a strikingly unpromising and thin interpretation of greeting and gift giving, given the complex wider environment I have drawn attention to.

In Cuffari’s et al’s dialectics, evolutions are simplified to fit a prior conceptual model. The theory isn’t built on multiple observations, but rather develops a theoretical explanation according to a particular logical frame. The study is therefore neither of language use as such, nor of a pure abstraction. It presents a particular hypothesis about how language ought to work given autopoiesis and dialectics.

The first model claims there are original tensions in social encounters. This is hardly new or surprising in terms of tension, since very few observers or participants have observed that social interaction is always peaceful and easy. A lot depends on what is meant by tension, since this could be any combination of productive differences, deep contradictions, violent oppositions, profound misunderstandings, unsolvable disagreements, or negations that can be overcome in new normative syntheses.

The claim that the tension is original is more unusual. It is a logical consequence of the presupposition of autopoiesis combined with subsequent encounters with environments. These later events are necessary for autopoiesis yet inconsistent with its norms and self-production. Autopoietic theory posits, rather than observes, the ensuing tension. It defines it through a form of original (‘fundamental’) precariousness of the autonomy of autopoiesis:

Thus an autonomous system is a network of interdependent, recursively enabling processes that sustain themselves under precarious conditions (Di Paolo 2005, 2009; Di Paolo and Thompson 2014; Thompson 2007). The notion of autonomy can thus be applied to an organism, or to a cognitive agent, or even to

Cuffari et al, p 1097

spontaneous relational patterns that emerge during a sustained social interaction.

Precariousness is a condition for the detailed definition of autopoiesis as a repeating system (a closed circuit) of processes capable of changing themselves and of supporting and changing each other. This is because each process is insufficient in three ways: it needs to change itself but with no certainty as to the outcome of that change; it depends on other processes but doesn’t have full control over the interaction; and all the processes depend on external environments and couplings that threaten them (a coupling is a closed autonomous interaction between two or more autopoietic processes).

Each insufficiency is a moment of fragility because it opens up processes to events beyond their control: in any recursion, a process might or might not manage to recreate itself in a new way; any interaction with other processes in the system might or might not break down; an external dependence might or might not introduce an existential threat to the system:

In this view, a body is a precarious system under-determined by its internal processes (biology) or external relations (social norms, power), but with a remainder of self-determination that involves the conditioning of body as a whole on itself. The body is constantly buying time for itself, inherently restless due to the unavoidable instability of its material constituents, and inherently in need of relating to the world in terms of significance if its form of life is to be sustained.

Ibid.

The key terms here are under-determined, self-determined and time. The first explains precariousness, because the lack of determination introduces uncertainty and potential for disruption and failure, from internal and external sources. The second explains closure and autonomy, since according to autopoietic theory living processes must retain a kernel of independent self-production. The third is the deepest flaw of a concept of individual precariousness. Time extends far beyond the individual and in ways it has but the most tentative grasp or control over. How can you know how your extension over time is precarious?

The concept of autonomy is frequently depended upon in autopoietic theory, due to its importance for the ‘auto’ of autopoiesis: the independence of the self-creator or self-legislator. In this instance, autopoiesis refers to the autonomous development and application of norms in the use of language to make sense of self-production, interactions and environments. Language use and sense-making are understood through a dialectical method building up from simple communication to fully developed social exchanges through the resolution of tensions according to norms or rules (do this don’t do that; if this, then that).

The method and resulting models are a response to a deep problem for autopoiesis and language. In complex social exchanges using language, it is highly implausible that actors are autonomous with respect to the rules governing that use, to the meaning of language, to the selection of words and phrases, to the responses of other actors, and to the effects of language on actors.

Lewis Carroll mocked the idea of autonomy in language through Humpty Dumpty’s haughty insistence on his control over words:

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.”

https://blog.oup.com/2022/11/the-return-of-humpty-dumpty-who-is-the-ultimate-arbiter-of-meaning/

Words don’t mean what you want them to mean in any of these cases: when others interpret your statements (No that’s not what I meant to say); when your choice of words alters language and your environment and yourself (I wish I hadn’t put it that way); when you have to link words to other words in your statements and become your own reader (I’m a stranger to my own word flow); when words take on a life of their own, impacting your feelings and thoughts before you have even started to try to put them into new words (That wounding phrase kept coming back, no matter how hard I tried to banish it.)

The rules of language, its meanings, the reasons behind linguistic choices, the patterns taken by statements and answers, and the emotional, unconscious and physical effects of words and phrases aren’t a matter of choice or autonomy for participants. They are restrictions and opportunities, guidelines and impulsions, influences and forms for complicated connections of actors in societies. Even if there is leeway for original interventions, these are shaped and conducted by language in ways that deny autonomy.

The enactive dialectical strategy seeks to get round this problem in two ways. First, simple exchanges are explained in terms of autonomous processes reacting to changing circumstances by adapting their internal norms. Second, the simple cases of autonomy are then expanded into ever more complex exchanges according to a problem-solution model.

This development is driven by the challenge of how to maintain the autonomy found at the more simple levels in more complex and less promising ones. The point is to show how intricate social uses of language require autonomy against appearances, because the autonomy present in more simple cases is still needed in the more complicated ones.

This strategy does not focus on autonomous language use as such, in the sense of generating statements. Instead, autonomy is in relation to the rules of that use. These are taken to be operated autonomously, that is, selected and developed independently of external control. We are autonomous in the norms we select and use for linguistic communication.

There is an explicit Hegelian reference in this synthetic resolution of tensions and dialectical methodology: ‘A resolution of this potential threat to the social encounter that keeps the advantages of community-sanctioned social acts is reached if participants mutually recognize their own autonomies in Hegelian fashion.’ (1106) For Hegel, mutual recognition solves the tensions of the master-slave dialectic. For enactivism, mutually negotiated norms, alongside individual norms, solve the tensions of social encounters.

Like Hegel’s commitment to recognition, the enactivist argument preserves specific content (autonomy and normativity) rather than mere logic (thesis, antithesis, synthesis) in the development. The danger in doing this is that the preserved content might greatly misjudge the nature of what is synthesised and how it can be so.

For instance, norm-based recognition is an unreliable and unfair way of resolving problematic social encounters, if those norms distort the nature of differences, or if recognition conceals further inequalities (for instance, of ownership, gender, sexuality, race, privilege, education, linguistic advantage, or access to law). The enactivist approach to language involves normative utopianism: the validity of its norms is ideal and hides continuing conflicts and pernicious influences. The ways we are passive to language are hidden in favour of an illusory autonomy.

The concept that reveals this flaw most strongly is the ‘individual embodied norm’. The following passage shows it most strongly in the conjunction of norm acquisition and autonomous identity. If norms are linguistic, then they carry the language, learning and environments of earlier acquisitions. There is no continuity of autonomy and individuality here, but rather a continuity of the influence of wider events and language, of the work of sense on norms, not the validity of individual sense-making for norms:

A single agent acts and makes sense according to her individual embodied norms. These norms, according to enaction, relate to the continuity of various forms of autonomous identity, or forms of life converging in the embodied individual (norms which are biologically, socially, and habitually acquired).

Elena Clare Cuffari & Ezequiel Di Paolo & Hanne De Jaegher, ‘From participatory sense-making to language: there and back again’ Phenom Cogn Sci (2015) 14:1089–1125 DOI 10.1007/s11097-014-9404-9, p 1100

For language users, there are no individual embodied norms and there is no individual autonomy, because language is at work as a multiple social and environmental influence in any action and in any change in a relative portion of an indivisible multiplicity of language users and life-forms. We are not autonomous parts of a jigsaw puzzle, but rather fluid and changing surface effects of a dynamic picture.

To refine its theory of language and sense, enactivism should rid itself of the autonomy of autopoiesis. The following conclusion perpetuates a distorting elision between acquisition and autonomy, because language does not disappear as an influence, it remains latent and influential in unpredictable and powerful ways, waiting to emerge in new events undoing the illusion of autonomy:

In summary, human embodiment (and in some different degree, other animal

1120

embodiments) involves a special kind of autonomy acquired via incorporation of

linguistic habits of sense-making. This autonomy relies on processes that are linguistic,

as much as other biological and cognitive processes. Otherwise, to repeat, we could not

explain where linguistic sensitivities come from.

What they should have said is this:

Human embodiment (any embodiment) involves a special kind of dependence acquired via incorporation of linguistic habit, carrying all of the past, present and future of sense and events. This dependence relies on processes that are necessarily linguistic because they involve signs. If we are to explain where linguistic sensitivities come from, we must abandon the concept of the autonomous individual and its own norms.

We don’t acquire language while preserving individual autonomy (the same is true for gifts and greetings). We continue to be acquired by sense and events. As they form and overwhelm us, we can experiment wisely in how to increase splendour and minimise woe.